Repost article: https://www.facebook.com/fabio.comana (Published date: 22 Jan 2018)

Author: Fabio Comana, M.A., M.S., Original Creator of ACE’s IFT™ Model, Faculty Instructor of NASM, Academic Consultant of FEA

Protein powder, a supplement once dominated by core users in body building and athletics and limited to specialty stores and gyms now targets a larger audience including fitness enthusiasts and health seekers who purchase their product in most mainstream retail stores. In 2013, U.S. protein supplement sales exceeded $7 billion, with protein powders accounting for $5.6 billion (77%) of that total – sales are expected to increase by over 40% by 2018.

Although the US government defines protein powders, bars, etc. as supplements, this product is predominantly derived from the process of making Mozzarella cheese; separating the curd (casein) from the whey. Furthermore, the process of producing whey isolates or concentrates is almost identical to the process of producing skim or low-fat milk from whole milk (i.e., micro- and ultra-filtration to remove fats, etc.). Yet, it is interesting that while milk and cheese are considered foods, protein powders are considered supplements. This does pose a potential concern over scope of practice given the lack of vigorous regulation of supplements under the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act (DSHEA) governed by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (3).

Under DSHEA, regulation of ingredients and banned substances is not ironclad. Subsequently, independent third-party agencies exist to voluntary test and validate protein supplements for quality/purity and ingredients.

• Informed-Choice (LGC Lab) is one such agency that provides quality assurance by certifying whether supplements and/or raw materials are free of any banned substances currently listed by the World Anti-doping Agency (WADA).

• National Sanitation Foundation (NSF International) is another supplement testing, inspection and certification organization who ensures product and ingredient safety.

Protein Quality

The term ‘protein quality’ is popular term used during protein discussion and reflects the amino acid profile of a protein food and how it mirrors the essential amino acid (EAA) quantities needed by the human body (i.e., RDAs).

Only the whole egg is considered 100% complete because its profile mirrors exactly what the body needs. All other foods, while not complete, contain at least trace amounts of all EAAs, but not in the ratios matching human EAA RDAs. The amino acid(s) not aligning with the EAA RDAs are defined as a limiting amino acids (LAA). For example, cow’s milk is a great source of protein (8-9 grams of quality protein per cup), but holds smaller amounts of methionine in comparison to the RDA needed by the body – milk therefore has methionine as its LAA.

Because milk protein is the most popular protein supplement source, it makes sense to discuss it in more detail. Milk is approximately 87% water, but remove the water and what remains is approximately 38% lactose, 27% fat, 27% protein and 6% minerals, ash and other materials. Of the milk proteins, approximately 80% is casein, whereas only 20% is whey, explaining in part why whey costs so much more than casein protein.

• Casein represents a group of insoluble proteins that form a gel (clot) in stomach when it mixes with stomach acids (much like milk curdles when bacteria feast on milk sugars and release acids) – this slows gastric emptying significantly providing the body with a true ‘slow protein.’ This provides a sustained (slow) release of amino acids into blood which can last several hours and prolong muscle protein synthesis (MPS) long after the completion of a workout. Casein is a good source of branched chain amino acids (BCAAs) and glutamine, both of which are believed to contribute positively to MPS and muscle recovery.

• Whey is a soluble protein that empties rapidly from the stomach, therefore becoming rapidly assimilated into body (whey isolates can enter blood within 15-to-20-minutes after ingestion on an empty sotmach). It is mother nature’s ‘fastest protein’ (isolates/hydrolysates) that supports MPS in the immediate hours following a workout. Whey protein is a richer source of BCAAs and glutamine, containing approximately 24-25% more leucine than casein. Leucine is considered the all-important EAA which acts as the engine to drive MPS.

The separation of casein from whey produces a whey base, often used as a food filler (e.g., whey powder). Further removal of the other ingredients yields a concentrate and then ultimately an isolate which is more expensive, but contains a greater concentration of protein. A whey isolate hydrolysate is a protein chain to which digestive enzymes have been introduced to ‘pre-digest’ the protein before ingestion with a goal of enhancing absorption (i.e., relying less on normal enzymatic breakdown of protein chains in the stomach by the enzyme pepsin). But, because whey is already the fastest digesting protein, no real difference exists by which slightly faster absorption results in any additional MPS effects in healthy individuals.

When making a protein choice, it is important to not base or limit your choices to what you read on a food label. Although a detailed food label providing amino acid profiles provides valuable insight into protein quality, how well the amino acids are absorbed into the body is equally, if not, more important. If the body cannot digest, absorb, and subsequently utilize the amino acids, then the protein is essentially ineffective. The latest evaluation system approved by the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) for quantifying protein quality and absorbability is called the Digestible Indispensable Amino Acid Score (DIAAS) which has now replaced the protein digestibility corrected amino acid score (PDCAAS) method that was introduced in the 1989 to assess protein quality and absorbability. This new system more accurately evaluates the amino acid profile and the food’s absorbability into the body. There is tremendous value in knowing a food’s DIAAS because it helps distinguish between quantity (i.e., how much protein is consumed) from quality (i.e., how much is absorbed into the body). This scoring is also very useful when debating the virtues of animal- versus plant-based proteins. For example, the protein found in peas contains an impressive amino acid profile (in fact the amount of leucine in pea protein is higher than in milk-based proteins), but it is absorbed less efficiently than milk protein. As a basic guide, animal-based proteins generally hold a superior EAA profiles and demonstrate greater absorbability when compared to plant-based protein.

Table 1-2: DIAAS for commonly consumed protein sources.

Protein Source DIAAS

Whole milk 1.32

Whey protein isolates 1.25

Whey protein concentrates 1.10 – 1.22

Whole eggs 1.13

Beef 0.90 – 1.10

Chicken 1.08

Soy isolate 1.00

Pea isolate 0.95

Oatmeal 0.84

Sunflower seeds 0.67

Chick peas 0.66

Peas 0.64

Barley 0.58

Rice 0.57

Kidney beans 0.51

Peanut butter 0.46

Wheat 0.40

Almonds 0.40

An additional factor to consider when comparing animal-based proteins against vegetable-based proteins is caloric density. For example, when comparing one large egg against a ½ cup of raw quinoa, they both contain a comparable amount of EAAs (3.5 grams) although the whole egg is a complete protein with no LAA. The issue with quinoa is that, as a food, its caloric density is significantly higher than that of the egg – approximately 240 kcal more for serving which, when consumed everyday will amount to 25 pounds (11.4 Kg) of weight per year. By contrast, when comparing the quantity and quality of protein between a comparable caloric serving of whey isolate and hemp protein, there is an obvious protein difference.

Egg (1 large)

(1) Approx. 3.5g EAA

(2) LAA: None

(3) Calories: 60-75

(4) Cost: Inexpensive

Quinoa (½ cup raw)

(1) Approx. 3.5g EAA

(2) LAA: Tryptophan and Methionine

(3) Calories: 315

(4) Cost: Inexpensive

Whey Isolate (25g protein powder)

(1) Approx. 9.1g EAA

(2) LAA: Methionine

(3) Calories: Approximately 100-120

(4) Cost: Moderate

Hemp (25g protein powder)

(1) Approx. 3.1g EAA

(2) LAA: Tryptophan, Histidine, Lysine and Isolelucine

(3) Calories: Approximately 100-120

(4) Cost: Moderate

Drinking a protein shake after resistance-training is a popular nutritional strategy adopted by many fitness enthusiasts and athletes to boost muscle protein synthesis (MPS), but does evidence support this practice, and if so, then what type of protein is best, how much should be ingested and when should it be consumed?

A common misconception with exercisers is that ingesting more protein supports greater levels of MPS, but the latest position statements from the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (AND), Dietitians of Canada (DC), the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM), the National Strength and Conditioning Association and the International Society of Sports Nutrition dispute this belief. They have each provided recommended dosages for endurance and resistance-trained individuals, as well as upper thresholds for protein intake. The notion behind establishing an upper threshold is based upon research that fails to demonstrate increased levels of MPS when eating more protein (i.e., exceeding the daily total or suggested amount in one meal because it (a) not be fully absorbed or (b) may not be utilized for muscle protei nsynthesis (MPS) by the body. Although these position statements do differ slightly between agencies, a consensus is presented below as a guideline for practitioners:

(a) 1.2 to 1.4 grams per kilogram of body weight (0.55 – 0.64 grams / lb.) for endurance-trained individuals (defined as greater than 10 hours per week of endurance-type training)

(b) 1.4 to 2.0 grams per kilogram of body weight (0.64 – 0.91 grams / lb.) for strength-trained individuals*.

For example, a 154-pound (70 Kg) endurance athlete would consume between 84 and 98 grams of protein (154 lbs. x 0.55 and 0.64), whereas a 220-pound (100 Kg) power athlete would consume between 140 and 200 grams of protein (220 lbs. x 0.64 and 0.91).

* A traditional dosage often used by individuals is 1 gram per pound of body weight or 2.2 grams per kilogram, a dosage that is about 10% higher than the upper threshold recommended.

However, it is also important to recognize that studies do exist that have examined higher protein intakes in experienced body builders and resistance-trained individuals who consumed high protein diets (up to 2.8 grams per kilogram or 1.27 grams per pound). These individuals continued to demonstrate MPS without any health concerns such as compromised renal function.

Another relevant question pertains to the quantity of protein that should be consumed within one meal or one sitting. Protein absorptive rates vary tremendously between people and between protein sources. Although males generally have a larger gastrointestinal (GI) tract, thus can absorb more protein than females, the reality is that it is very difficult to accurately determine this quantity given the myriad of factors that influence protein digestion and absorption rates which include:

(a) Protein digestibility efficiency of foods (differs between plant and animal sources).

(b) Body size and genetics.

(c) Meal size and composition (presence of fiber and fats can impede protein absorption).

(d) Protein sources (e.g., whey, casein, egg). Whey being water soluble is absorbed more rapidly than casein, an insoluble milk protein that forms curds in the stomach, retarding its gastric emptying and absorption for hours. An egg on the other hand contains six to seven grams of protein, yet the body absorbs approximately 3-grams of cooked egg each hour.

(e) Diet experience (individuals consuming higher protein intakes may adapt to digest/absorb protein more efficiently).

A study by Symons and colleagues compared 30 grams of protein versus 90 grams on MPS in young and elderly groups. Their research demonstrated that ingestion of more than 30 grams in a single meal did not further enhance the stimulation of MPS in both populations examined. This value echoes much of the sentiment of other researchers who estimate that between 20- and 30-grams represent an ideal protein quantity that can be efficiently absorbed in one sitting. Dosages therefore, of approximately 20 grams for women and 25-30 grams for men in one sitting appear ideal, subsequently necessitating multiple feedings throughout the day to reach a desired total.

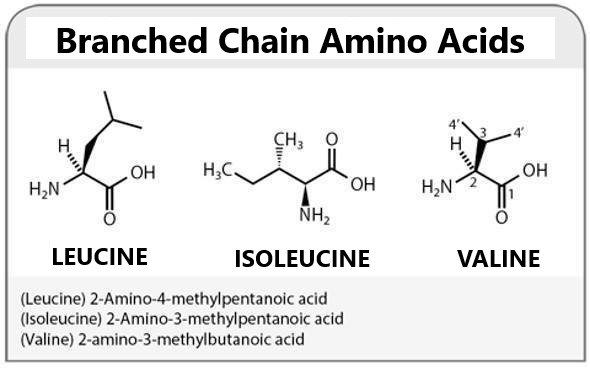

What appears to be garnering much interest in muscle protein synthesis (MPS) research is the quantity of leucine consumed. Amino acid metabolism in skeletal muscle is generally limited to 6 amino acids (glutamate, aspartate, asparagine, BCAAs – leucine, isoleucine and valine), but the most significant effects are tied to leucine which acts as a critical regulator of MPS (e.g., mTor muscle synthesis pathway), complementing insulin’s signaling effects and the production of other amino acids in muscle development (think of leucine as the engine or switch to drive MPS). Current consensus appears to agree that a minimum dose of around 2-to-2.5 grams of leucine is needed per feeding to signal the mTOR pathways that there is adequate dietary protein present to support MPS.

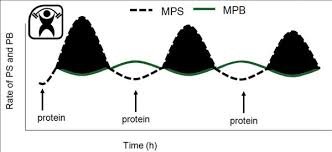

Protein timing is critical to enhancing MPS and muscle recovery. Although it has demonstrated that pre- and post-exercise protein ingestion results in increased rates of MPS in comparison to morning- and evening-feeding, differences between pre-exercise and post-exercise remain less clear. Tipton and colleagues fed active individuals an amino-acid-carbohydrate beverage containing of 6 grams of essential amino acids (EAA)* and 35 grams of a high-glycemic carbohydrates (EAA-CHO) 60 minutes before high-intensity resistance training (80% of 1 repetition max – RM) and within 30-to-45 minutes following that same workout. The study revealed that the net MPS associated with pre-exercise protein intake was greater than protein consumed after exercise. However, this finding was not replicated in a study by Schoenfeld and colleagues who found no differences between pre- and post-exercise ingestion of 25 grams of protein. Although this study also concluded that the optimal post-exercise anabolic window for maximizing MPS is also not as small as once believed (i.e., 2-3 hours post-exercise), but rather extends for 5-to-6 hours, other studies do not support this same finding, and recommend protein intakes within the first hour post-exercise.

* 6 grams of EAA is equivalent to 17.5 grams of pea isolate or 12 grams of whey isolate (excludes consideration of protein absorbability where pea isolate is approximately 75% of the efficacy of whey isolates).

Applicable takeaways may be one where a dose up to 20-to-25 grams of protein is consumed within the hour before exercise, and then consumed again within the first hour post-exercise. The consensus of research on protein consumption in the post-exercise window is a dose of 20 grams, but this amount can be more specifically calculated using a dosing range of between 0.25 to 0.3 grams per kilogram (0.11 to 0.14 grams / pound) (11, 19). For example, a 176-pound (80 Kg) individual would aim for a protein intake between 20 and 24 grams of protein.

Previously, I reviewed key differences between quality and the absorbability of plant- versus animal-based proteins, and between proteins within each food category. The most important outcome of protein consumed either before or immediately following exercise is rapid delivery to the muscles cells – ‘fast’ proteins deliver amino acids to the muscles more efficiently.

Whereas casein can take hours to empty from the stomach, whey isolates can enter the blood within 15-to-20 minutes. Subsequently, individuals would be best served by consuming a fast protein like a whey isolate before and/or after their workout. But, because protein should also be consumed several hours later (e.g., 3-4 hours), an alternate strategy post-exercise is to consume a blend of both fast and slow proteins for the sake of convenience considering how some individuals may not have the inclination of ability to eat again several hours after their workout. Whether the inclusion of a slow protein with a fast protein (i.e., blended protein) impedes immediate MPS is largely unknown. Regardless, protein intake throughout the day should ideally follow a regimen of frequent, smaller protein dosages to sustain more a positive nitrogen balance (i.e., preserving muscle mass rather than breaking it down). Preferably, this entails a practice of ingesting quality protein every few hours (e.g., 3-4 hours) and complemented by the ingestion of a ‘slow’ protein like casein before bed to help reduce the catabolic state the body experiences during an overnight fast.

Although post-exercise protein shake consumption remains a viable and effective practice, we should consider other evidence-based strategies so that we can optimize outcomes associated with the practice of consuming additional protein.

Footnote: The consumption of branched-chain amino acids (BCAAS – 7-25 g / hour of exercise) during exercise is believed to reduce post-exercise muscle soreness and accelerate recovery, although this research is not without controversy.

Don’t forget to catch Fabio Comana (Original Creator of ACE’s IFT™ Model, Faculty Instructor of NASM, Academic Consultant of FEA) in the FEA Mini Workshop 10: Get The Protein Scoop – Pre, Peri And Post Exercise Protein Timing (Virtual) to get the most updated guidelines and researched related to protein and fluid intakes, the timing, type, and quantities needed before, during and following exercise. Registration link: https://fit.com.my/course/fea-mini-workshop-10-get-the-protein-scoop-pre-peri-and-post-exercise-protein-timing-virtual/

Featured Videos

Featured Industry Insights Videos

Mentor Corner #4: Are All PT Certifications Created Equally?

Exercise Techniques Featured Videos

BENT OVER ROW: Here’s how to do it.

Biomechanics Exercise Sciences Featured Videos

Kinesiological Concepts: Force Couples #1

Articles Featured

? ????? ?? ??????? ??? ?????? ?????-?? ????????/ ? ??????? ??? ?????? ???????? ?????-??/ ? 个步骤: ?????-?? 疫情期间 心肺复苏术( ???)

Articles Featured

The Latest Scoop – Protein Supplementation and Things to Know (Published date: 22 Jan 2018)

Articles Featured

職涯發展